I'd Rather Be Blind

The night hides a world but reveals a universe.

My life after Afghanistan.

By Grant Lock

Grant Lock directed Afghanistan’s largest eye care program. Until he himself became blind. He returns home to a society with its own blind spots: myopic attitudes to Islam, mental health and what makes us human. After battling corruption, injustice and disadvantage in the deserts, mountains and cities of Pakistan and Afghanistan, Lock confronts challenges—both intimate and global—with courage and compassion.

| 1 | Blasphemers will die | 13 |

| 2 | The salesman | 15 |

| 3 | In love with the garbage man | 19 |

| 4 | Macular wall | 23 |

| 5 | Widow of the curly comeback | 27 |

| 6 | The fur piano | 31 |

| 7 | Frishta goes shopping | 35 |

| 8 | Hanging out | 39 |

| 9 | The gun | 41 |

| 10 | The road not travelled | 45 |

| 11 | Some of your children will die | 49 |

| 12 | Survival at Sandspit | 51 |

| 13 | Who? | 57 |

| 14 | The Lamborghini and the big stick | 61 |

| 15 | Road therapy | 65 |

| 16 | Holding on | 67 |

| 17 | Lost | 71 |

| 18 | Flowers and phones | 75 |

| 19 | The plainclothes policeman of Kabul | 79 |

| 20 | Mobile Mo | 83 |

| 21 | The commander and the flood | 85 |

| 22 | Liars, twisters and fools | 89 |

| 23 | Young Lawrence of Arabia | 91 |

| 24 | Double dilemma | 95 |

| 25 | Out of your brain | 97 |

| 26 | The package | 103 |

| 27 | The man | 107 |

| 28 | The delivery | 111 |

| 29 | The Basant trap | 113 |

| 30 | Sadiq Sahib | 117 |

| 31 | Cat and mouse | 121 |

| 32 | Silent night | 125 |

| 33 | Will the real Islam please stand up? | 129 |

| 34 | The club | 133 |

| 35 | The last straw | 137 |

| 36 | And one thing more | 141 |

| 37 | Land-locked Afghanistan | 147 |

| 38 | Stop picking on us! | 149 |

| 39 | Melons | 153 |

| 40 | The fifth face | 159 |

| 41 | Never say never | 161 |

| 42 | That woman | 165 |

| 43 | Miscalculation 1 | 169 |

| 44 | The pervert | 171 |

| 45 | Miscalculation 2 | 175 |

| 46 | Fumes | 179 |

| 47 | Welcomely obscene | 181 |

| 48 | Flashman | 183 |

| 49 | The rifle | 187 |

| 50 | And the winner is … | 193 |

| 51 | The touch | 197 |

| 52 | The squatters | 199 |

| 53 | When the planets align | 203 |

| 54 | Healing | 207 |

| 55 | The last Wali, the Mad Mullah and Malala | 215 |

| 56 | Julietta | 223 |

| 57 | Tsunami | 227 |

| 58 | The left side | 229 |

| 59 | Finding the mastermind | 231 |

| 60 | Two dollars’ worth | 237 |

| 61 | The crab girl | 241 |

| 62 | Hubble images | 245 |

| 63 | The muddy morgue | 249 |

| 64 | Faces of death | 251 |

| 65 | Keemia | 255 |

| 66 | The Afghan wedding and the drummer from hell | 257 |

| 67 | The cigarette | 261 |

| 68 | Grounded | 265 |

| 69 | Flotsam | 267 |

Riveting. To his experience in some of the world’s most troubled places, Lock brings a bushman’s wit and wisdom. Lock writes about Islam with authority and insight.

Grant Lock is master of the ripping yarn. This smorgasbord of human experience spans centuries and continents and embraces themes common to us all: hostility and hospitality, disaster and hope, the mundane and the marvelous.

Inspirational. I could sit in a pub all day listening to Grant Lock.

I thank God for you every day.

Grant Lock dug wells, built schools and helped restore the eyesight of thousands of Afghans. Grant is married to Janna, the woman the widows of Kabul call Frishta (Angel). Development work in Pakistan and Afghanistan followed their notable success as cattle breeders in South Australia.

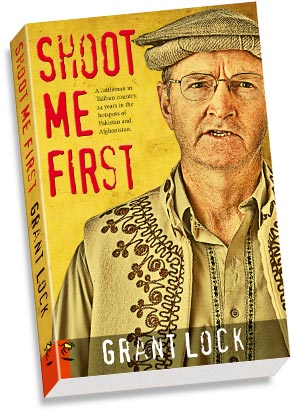

Shoot Me First

A cattleman in Taliban country.

Twenty-four years in the hotspots of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

By Grant Lock

Shoot Me First is a gripping personal account of life in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The author offers intriguing insights into the culture of the tribal territories that straddle the two countries. This is home to the Taliban, an untamed land which continues to absorb so much of the world’s attention and military endeavour. Lock is shrewd and laconic but above all compassionate. His experience of the world’s two major religions deserves careful consideration.

Supporting micro-hydroelectric systems, empowering Afghan widows and overseeing a massive eye-care program, Grant and Janna Lock’s development work in Afghanistan and Pakistan followed their notable success as cattle breeders in South Australia.

Supporting micro-hydroelectric systems, empowering Afghan widows and overseeing a massive eye-care program, Grant and Janna Lock’s development work in Afghanistan and Pakistan followed their notable success as cattle breeders in South Australia.

| Prologue | 15 | |

| The Desert South-East Pakistan 1984–1989 | ||

| 1 | Half way across Australia | 21 |

| 2 | A name to remember | 23 |

| 3 | We the beggars | 27 |

| 4 | Perfume and punches | 31 |

| 5 | The unwanted woman | 37 |

| 6 | The arrangement | 41 |

| 7 | It’s in our blood | 45 |

| 8 | A window in the desert | 49 |

| 9 | Bhopa anyone? | 57 |

| 10 | Son of the prostitute | 61 |

| 11 | Rocky rip-off | 67 |

| 12 | A crack in the caste | 77 |

| 13 | Too fat for mujh | 87 |

| 14 | Putting off or putting on | 91 |

| 15 | Almost orange marmalade | 97 |

| 16 | The waiting room | 101 |

| 17 | Swissair scare | 105 |

| 18 | Fries your brains | 109 |

| 19 | Good news, bad news | 113 |

| 20 | Gardening the Taliban | 121 |

| 21 | The spies go north | 125 |

| 22 | Midnight movements | 129 |

| The Frontier

North-West Pakistan 1989–1998 | ||

| 23 | Flower power | 141 |

| 24 | Secrets | 145 |

| 25 | Tennis anyone? | 151 |

| 26 | Fata | 155 |

| 27 | Gun town | 165 |

| 28 | Shoot me first | 171 |

| 29 | The sickening thud | 177 |

| 30 | Royalty | 181 |

| 31 | Special meat | 189 |

| 32 | Not a bad innings | 195 |

| The Capital

North-East Pakistan 1999–2003 | ||

| 33 | The snow princess | 205 |

| 34 | Kabir takes a wife | 209 |

| 35 | Retribution | 215 |

| 36 | The throat cutter | 221 |

| 37 | Mrs Baitto | 225 |

| 38 | Blood on the ceiling | 231 |

| 39 | Do I know you? | 235 |

| 40 | Counterfeit cricketers | 239 |

| 41 | The Uyghur reunion | 247 |

| 42 | Vaporised | 249 |

| 43 | Meet me under the bridge! | 251 |

| 44 | Only kafirs ask questions | 255 |

| 45 | Training terrorists | 259 |

| Taliban Country

Afghanistan 2004–2008 | ||

| 46 | The return of the blue-eyed boy | 269 |

| 47 | Before the fall | 275 |

| 48 | It’s a man’s world | 281 |

| 49 | I sold my baby | 285 |

| 50 | The charmer | 291 |

| 51 | Go to hell | 295 |

| 52 | The sweetheart and the setup | 297 |

| 53 | The Smith and Wesson | 301 |

| 54 | The lama of Elista | 305 |

| 55 | The mask | 309 |

| 56 | The beautiful eyes | 313 |

| 57 | The Chinese singer | 319 |

| 58 | The surprise | 323 |

| 59 | The elephant in the room | 325 |

| 60 | Deep pockets | 333 |

| 61 | Number 17 | 339 |

| 62 | In the chair | 345 |

| 63 | Back in the barn | 349 |

| 64 | Afghan angels | 355 |

| 65 | One-way street | 359 |

| 66 | Pul-e-Charkhi prison | 365 |

| 67 | The tree hugger | 373 |

| 68 | Cafe Omar | 379 |

North-west Pakistan, 1992

The stench of stale urine rises with the dust as my Pakistani workmen begin to demolish the building. Shovels and picks bear down on the mud bricks, clay rendering and poles. Sweat rolls down their faces, glistening in the sun.

Time is up. The dukandar (shopkeeper) has had his chance to demolish it himself. Now I’m doing it for him, as quickly as I can, before there is trouble. I’m dimly aware of the noise of a crowd gathering in the street outside the mud walls of the derelict Pennell High School.

This is Bannu, in Pakistan’s Pashtun country, near the border with Afghanistan. Back in the days of the British Raj, Dr Theodore Pennell built a school for boys and later added this segregated compound for girls. Neglected, and closed in recent times, we plan to open it again.

It is a challenging region for an engrez (foreigner) to work in. Before too many years have passed, the eyes of the whole world will focus on the nearby rugged Tribal Area. The Taliban- and al-Qaeda-riddled mountains span this porous border of the Islamic Republics of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Pilotless drones will circle overhead while Islamic extremism oozes from its mountain fastness. As the Coalition tries to extricate its troops from the Taliban war, Afghanistan will be worried. The United States will be worried. Indeed, the entire world will be worried because the sting of an over-patronised Taliban scorpion will be curling back to strike its mentor, nuclear-loaded Pakistan.

Now in 1992, however, as I watch the walls of the dukandar’s illegal storeroom come down, all I’m worried about is getting the job done despite any uncooperative locals.

“Sir! Now! You must come now! They are very upset!” It’s Samson, my dedicated Pakistani assistant. Unlike the long-haired muscle man of Old Testament times, my Samson is frail and sickly. He stands barely as high as my shoulders. But his shrewd understanding of Pashtun ways has got me out of jams before.

“Sir! Sir! You must come outside! They have guns!”

So what’s new? As with the naan bread and chai tea they survive on, Pashtuns and guns are synonymous. Pashtun boys are born with a gun in their hands. Pashtun courage and marksmanship when repelling invaders and settling feuds amongst each other are legendary.

“Look, Samson, this building is coming down. Right now! We need all the space we can get to rebuild the school.”

“Voh bahoot bahoot naraaz!—They are very, very angry, Sir!”

Pashtuns and guns, plus anger. I’d be a fool to ignore that nasty cocktail. I order the workmen to keep up the demolition. Dust from the collapsing clay roof fills the air as I march to the gate. It was hard enough to evict the squatters. We’re not stopping now.

Stepping out of the compound, I can see that the influential shopkeepers have indeed stirred up an angry crowd. Mostly bearded, they are gesticulating and shouting in Pashtu. What’s all this about? They know their fellow shopkeeper illegally extended his storeroom into the school ground. They know that yesterday he signed a document admitting his fault. He agreed for us to remove the building if he failed to do it himself within twenty-four hours. Surely they know that we are re-opening Pennell’s school for their Muslim daughters as well as the minority Christian girls. Don’t they realise that this is for them?

But the mob is defending the damaged honour of their colleague, who yesterday had to publicly admit his guilt to an unbelieving foreigner, a lowly kafir who stands with the small community of Pakistani Christians, the local kafirs.

Hospitality, honour and revenge. That’s the age-old mantra of Pashtunwali, the unbreakable code of the Pashtuns. Looking into the black eyes of the shouting beards, I can see that in this dusty Bannu bazaar, honour and revenge have conveniently coalesced.

The mob surrounds us. Samson’s glasses seem bigger, and his body smaller, than ever. The mob’s burly leader shouts in Urdu, a language that has taken me three years to master. “If you don’t stop your workmen from demolishing the building”—and he pauses to add venom to his ultimatum—“we are going to shoot them!”

The crowd falls silent, savouring the imminent back down of the engrez. The preservation of all-important male honour trumps female welfare every time. Anger and indignation surge up within me. Hey, you bellowing misogynists, this is for you. This is for your daughters, for the mothers of your grandchildren.

I stare back. Who is going to blink first? My brain fleetingly recalls a girl I met the day before. “I want to study,” she confided. “One day I want to become a doctor.”

The emboldened beard repeats his threat. “If you don’t stop your workmen from demolishing the building, we will shoot them!”

I hear my voice answering the challenge. It’s surprisingly strong and resolute. “If you are going to shoot my workmen, Sir”—and I jab my forefinger, first at his chest then mine—“you’ll have to shoot me first!”

They all hear it. The silence thunders in my ears.

Crisp, beautiful and revealing. Valuable for anyone trying to build an appreciation of Islamic societies. And that should be all of us.

Lock’s adventures are probed for meaning so that the reader may have a deeper comprehension of a region frequently in our headlines but seldom in our understanding.

The raw reality of daily life for ordinary people, up close and personal. Lock gives the most pressing global issues of our time a human face.

Your book brought back so many memories. I couldn't help but cry.